Recap: In Part 1 we saw just how dependent Europe is on Russian gas (38%), coal (46%), and oil (23%). Russia’s energy sector accounts for 40% of it GDP, so taking that away can work to halt the war machine. In Part 2 I proposed some short-term measures that can take the EU a few steps toward energy independence: starting up recently shut down nuclear units and stations, and re-supplying a proportion of gas from increased LNG export capacity in the US.

Now let’s create a best-case scenario to make the EU’s energy sector independent of Russia (and cleaner!) within the decade. It involves a lot of new generation from non-fossil sources, some efficiencies, and a lot of resupply from friendly partners.

Fossil fuel usage by sector

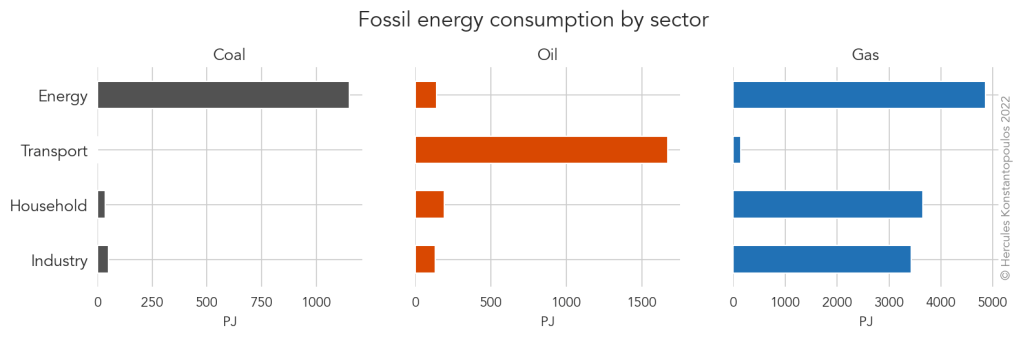

To come up with a plan we’ve got to look at how energy from fossil fuels is used across Europe. The data from Eurostat offer an exhaustive breakdown, so I will aggregate into four groupings that we can plausibly tweak with central planning and behavioural adaptation: energy generation, industry, transport, and household use.

Coal and oil are dominated by a single sector, but gas is more widely used. Let’s look at each fuel.

Coal

In terms of end use, there are two kinds of coal: metallurgical (black) coal used in coke ovens to turn iron into steel; and lower grade thermal (black and brown) coal used for energy and electricity generation. In Part 2 I suggested that we turn to Australia to swap the Russian coal supply. Let’s take a closer look at the data from Geoscience Australia.

Thermal coal dominates the fossil mix of Europe, with 36 Mt (Mega-tonnes) imported from Russia. This equates to 17% of Australia’s 2019 export of 210 Mt. That seems impossible to replace in a single transaction, but can we pencil a quarter of that to Australia plus other friendly nations? From Part 2 we know that Australia has reachable reserves of roughly 1750 years’ worth of Russian imports to the EU… they’re good for it and according to multiple Prime Ministers, they love digging up the stuff!

Maybe we can more easily offset coking coal. That’s 10% of the coal EU consumption, or 122 Mt. Thankfully, only 4 Mt came from Russia in 2020, which equates to 2% of Australian exports (0.9% of their 460 Mt of production). Let’s lean on Australia to provide all those 4 Mt.

This re-sourcing from Australia (and other friendly producers) immediately removes 30% of Russian coal imports. Now let’s model re-sourcing the remainder at 10% per year. We’ve removed all the coke coal in 2022, so we gradually remove thermal coal.

Oil

Imported crude oil is mostly shipped to refineries to become transport fuel. We can’t swiftly shift road transport: EVs are an obvious way out, but that’s just shifting the problem to electricity generation, which is still largely fossil-driven.

What about a 10% reduction through efficiency measures? Everybody takes nine trips in 2022 for every ten they took in 2021… it seems like an achievable wartime sacrifice. What else? We found out during Covid that a considerable part of the economy is able to operate with remote (desk) workers. This would help reduce oil for commuting. In 2020 Europeans burned through 232 Mt of fuel for transport, and imported 171 Mt from Russia. This 10% reduction in transport oil requirement would offset 14% of Russian oil import.

What about household use? Oil is used for heating and hot water through diesel-powered boilers in people’s basements. It’s outdated technology but it is expensive to swap for a viable, modern alternative, such as a heat pump or a wood pellet burner. Europe used 30 Mt of heating oil in 2020. Roughly equating that to two tonnes per home (that’s what we burned in the mountain home where I grew up), we get around fifteen million homes.

Can we immediately shift a third of that to heat pumps and wood pellet burners? Five million installations in a year sounds bonkers, and I am no expert on logistics and supply lines for this machinery. Wood pellet burners are made in Europe, as are some heat pumps (here in New Zealand they tend to be made in Japan), and there is capacity on the EU grid for 50 million heat pumps, so we are not breaking the electrification bank!

As an aside, I am a big fan of Saul Griffith’s message of the wartime-like mobilisation it will take to electrify the world—heat pumps being one of his main recommended tools. Seeing as we are in wartime, we can drop the “-like” from this verbiage and get to building heat pumps and wood burners.

What does that do? 19% of Russian oil offset by efficiency plus electrification and fuel-swap measures. Let’s model this time series by removing 20% of the remainder for heat pumps and wood pellet burners each year.

That’s considerable, but still a small dent from efficiency and electrification. Transport fuel is hard to move so the rest will have to come from re-supply. Let’s remind ourselves what proportion of production we’ll need from other partners: in Part 2 we worked out that the EU would need the equivalent of 15% of production from the US and Saudi Arabia, and 20% of Norway and the UK, which might be too much to ask (happy to be wrong!).

To make that feasible let’s ramp up gradually. If we start with 5% of production from each partner (adding up to 57 Mt) we can offset a third of Russian imports. Let’s now take into account the reduction scenario above, and on top of that apply alternative sourcing: 5% in 2022, and step up 1% each consecutive year.

The combination of new supply partners and replacement of houselhold oil-fuelled boilers with heat pumps and wood pellet burners harmonises in 2028. After that point no Russian imports are required at all. How much Russian oil does this scenario require?

We drop to 44% immediately, and then 10% per year to hit the bottom of that oil barrel in 2028. Oil is the main money-maker for Russia (even though they provide more gas). We can work out what these lost exports are worth in 2020 money. Keep in mind that (bulk) supply contracts will keep their value, but the spot price will change: with prices for Russian oil already showing signs of decline, this amount might end up being less.

(Side-note: even as Shell announced its exit from shared interests with Gazprom, it then bought Russian oil just one week into the conflict. Welcome to the complex and eye-wateringly frustrating world of energy).

The loss of income starts at €25 billion (in 2020 money) and increases by €3b each year. In 2022 that is €69 million per day in lost income for Russia.

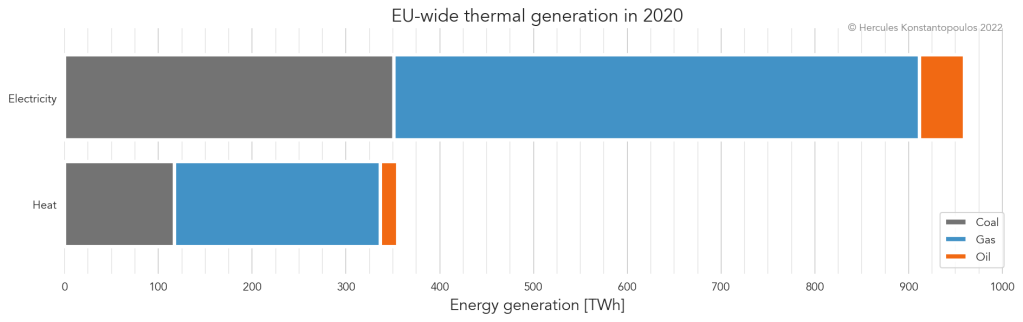

Gas and electricity generation

This is where the complicated nature of gas supply and usage comes into play. This section will get a little dense, so in a nutshell this is how I will construct my toy model:

- Check what stations are meant to come online this year and assume they will.

- For renewables, look at every record installation year and use as an optimistic baseline for annual increase.

- Connect Iceland’s geothermal generation through a submarine cable to the UK.

Low-carbon generation history

To get an idea of how much low-carbon generation we might install, let’s refer to historical data:

Lots to take in here. On the left we have capacity installed each year since 1990 for wind, solar photovoltaic, geothermal, and nuclear energy generation. The middle plot shows the complement (generation fleet) over time. And on the right we have the efficiency as the actual energy (GWh) produced in a year divided by the nameplate (GW) capacity times a year’s worth of generation. (Geothermal is a funny one as its energy can be used twice: once the electricity is dispatched, the hot geothermal ‘brine’ can be piped away from the plant for direct heat applications, such as home heating or industrial process heat. That makes its efficiency greater than 100%. Isn’t that cool?)

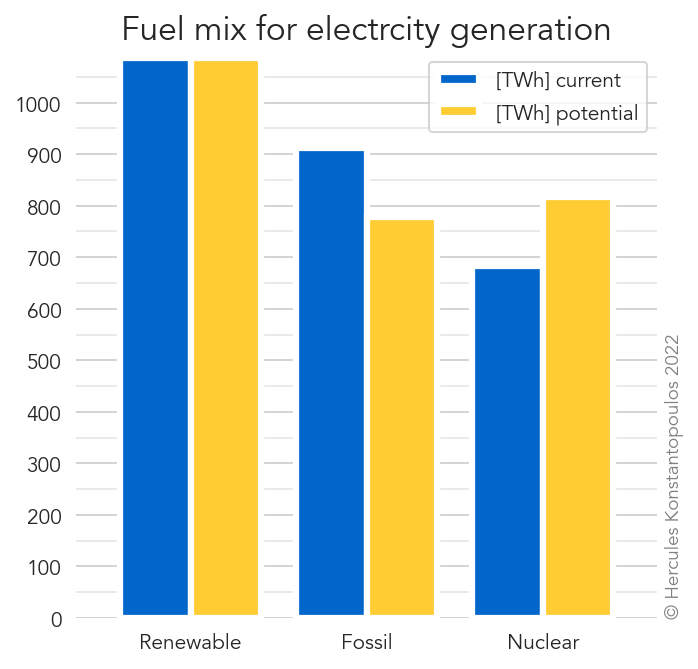

From this we can get the maximum plausible annual installation rate for new capacity. For solar and wind we get 22GW and 12GW respectively. We also have the EU pledge to increase wind capacity to 350 GW by 2030. Let’s work backwards from that number and evenly apply the excess needed to reach the goal. We had 177 GW of wind installed in 2020, meaning the EU aspires to add 173 GW in the coming eight years, or 21.6 GW per year. Let’s be ambitious and make it so (in our model, but hey, IRL too).

We can now use the above efficiencies to turn GW into GWh or PetaJoules (PJ) over the course of a typical year. An important caveat: from now on, when I compare electricity generation from renewables to that from fossils, I will be applying the thermal-to-electric conversion efficiency of 39%. This is a huge advantage of electrification from primary fuels: the photovoltaic effect for the Sun; the direct spinning of a generator by wind; and splitting atoms for nuclear. In other words we get a whole 1 Joule for every 0.39 Joules of fossil electricity we offset. Bonus!

With that conversion in mind, those roughly 45 GW per year of new wind and solar can offset 10% of fossil generation from Russian imports. That’s each year. It’s amazing.

Future nuclear

Let’s go back to this source to look for stations and units scheduled for completion this decade:

| Country | Station | Capacity (MW) | Completion date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | Olkiluoto | 1,600 | 2022 |

| France | Flamanville | 1,600 | 2023 |

| Slovakia | Mochovce | 880 | 2024 (assuming 15 years in construction) |

| UK | Hinkley C | 3,200 | 2028 (assuming 10 years in construction) |

The completion dates for Olkiluoto and Flamanville come from the source. For the other two I have assumed the historical average construction time in each locale.

Given the efficiency derived from Fig 6, plants coming online in 2022 and 2023 can each offset 2% of Russian-imported gas. Mochovce can offset 1%, and Hinkley can offset a mammoth 4%.

The IceLink cable

As I sat down to hypothesise whether a submarine high-voltage direct current (HVDC) cable between Iceland and the UK would be feasible, I found out this is in planning as a 1.2 GW connection.

There are two factors to consider: geothermal potential, and linkage distance.

This industry source claims Iceland can double its generation in an environmentally friendly way. There are about 3 GW of installed electricity generation right now, so there is potential for another 3 GW. The 1.2 GW HVDC des not seem too far fetched.

What about the cable itself? It’s about 1,000 km from Reykjavik to Scotland. This seems quite feasible when compared to the existing, 610 km long Interisland connection between the two islands of New Zealand. (Sun Cable, a planned connection between Australia and Singapore will run 5,000 km). Interisland took four years to construct in the 1960s, so it should be at least as fast to do this now, with bigger and better spool-carrying boats.

Let’s jot that down as 1.2 GW (350 GWh) for 2026 in an ultra-optimistic model. (I’m keeping the >100% efficiency; even though only the electrical segment is beamed through the cable, the excess will be used locally, and it’s a rounding error in the grand scheme).

A model for eliminating Russian fossil imports this decade

We have four sources of newly installed capacity: Solar is assumed to be installed at the peak rate, every year; wind follows the EU’s 2030 goal; nuclear follows the programme laid out above; and IceLink is assumed to come online in 2026.

That’s quite a marvellous vision for Europe, energy independence from Russia aside, the emissions reductions will be off the scale! And it’s not just Russia, this make Europe much more self sufficient overall.

Those are some encouraging numbers, but how do they compare to electricity generation from Russian fossils? Recall that in Part 2 we be replaced a bunch of gas with American LNG. Starting with that, let’s make a time series of further reductions, assuming we can re-source supply by 10% of the remainder each year. Then we can add up Russian coal and gas to a fossil generation bundle—oil is used for transport so it stands alone, not going past Fig 5.

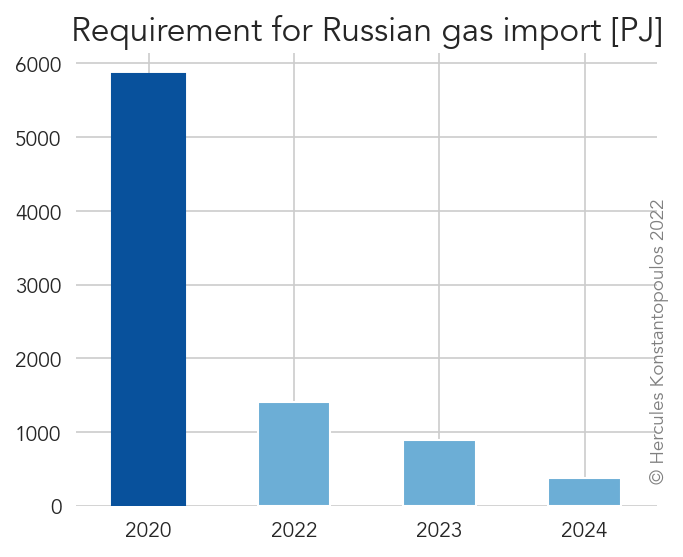

Let’s plot the reduction model from re-supply against the rise of new non-fossil generation:

New renewables and nuclear overtake electricity generation from Russian coal and gas in three short years. There are approximations and caveats here, primarily to do with the efficiency inherent in offsetting gas and coal used for electricity generation (recall that 39% thermal-to-electric conversion from fossils). The logistics are not as simple as I present here, they require a lot of shifting of gas between uses and sources, but this is in the realm of plausibility—it must be: as I go to press the EU is about to announce an 80% cut of their Russian gas import, and the US is moving to ban Russian oil altogether.

How much Russian gas does that leave?

Let’s again translate that into cold, hard cash (with similar caveats about spot prices). The value of 2020 coal and gas imports from Russia to Europe was €11.6 billion. That annual Russian income of €11.6 billion is lost within three years in this scenario. Combined with €25 billion per year (and increasing) for oil, how many tanks will Russia be able to afford without that money?

An independent, low carbon future

In this series I’ve laid out a European model of energy independence (and incidental decarbonisation) that relies on changing supply lines in the immediate term; building renewable generation at record rates; and introducing efficiencies through electrification and relatively easy behavioural change.

The model assumes that the consumer is fully in control of this relationship. But the supplier really has all the power. If the Kremlin decides to turn off the tap there will be an immediate and deep shock to the system that will require commensurate behavioural change. Faced with an inability to heat a good proportion of apartments in Europe, cohabitation might be a decent emergency measure. If you have elderly parents and a spare room, don’t let them get pneumonia, have them live with you—and if you or they can still afford their rent, pay at least some of it so Europe’s landlords don’t all go bankrupt. Conversely, if you have university-age children, get them back home. Companies that fared well with remote work, keep that going (and again, maybe pay those landlords). Crypto bros: just stop it. In any case, that’s a broad conversation for another time. If it comes to that we’ll react, and I’ll write another analysis.

The good news is how quickly this toy model removes the requirement for Russian imports. It’s all achievable this decade. And the positive effects to the environment will be astonishing. You don’t have to care about renewables to appreciate the clean air and water (and self-sufficiency).

The impact on Russia

This whole project has been about taking away 40% of Russia’s GDP and defund the war machine. The opposition of at least some Russian people to this war is exemplified by the thousands who took to the streets knowing they would be arrested… and then who knows what. While their country’s first foray into democracy didn’t work out, I hope they make their way out of these hard times by keeping up pressure on their regime.

Tough choices for the future we seek

The risk to humanity of an escalation to a new World War including multiple nuclear powers is immeasurable. You might not like a resurgence of nuclear energy, but the risk of fallout from nuclear warfare is total ecosystem collapse.

I am heartened by the swift action we’ve seen in the past two weeks. I’ve been very surprised to see leaders take charge—rather than polls and election feelers—and confront this monstrous invasion head on. Let’s see this through; energy independence is crucial to restore peace. Once we’ve got that in the bag, we can resume our work to make the world better—and all the carbon saved in the process will take us closer to that goal.